The complexities of electronic waste and it’s impact

Electronic waste (also called e-waste) is a collection of IT assets like anything with a plug, battery, or power cord that people throw away. This may include phones, laptops, monitors, TVs, printers, routers, and small gadgets. There are two aspects to E-waste: it can contain toxic materials (like lead, mercury, and cadmium) but it also contains valuable materials (like copper, gold, and other rare materials found in electronics).

The problem with e-waste is thus, complex and if handled the wrong way, it can pollute air, soil, and water. However, if done right the negative impact is minimized and can help protect the environment, recover value, and reduce the need for mining. That’s why recycling e-waste properly matters more than most people think.

Quick answer: The world is generating e-waste faster than recycling systems can collect and process it. Even when recycling rates improve, the total volume grows faster, so more devices slip into storage, landfills, or informal recycling.

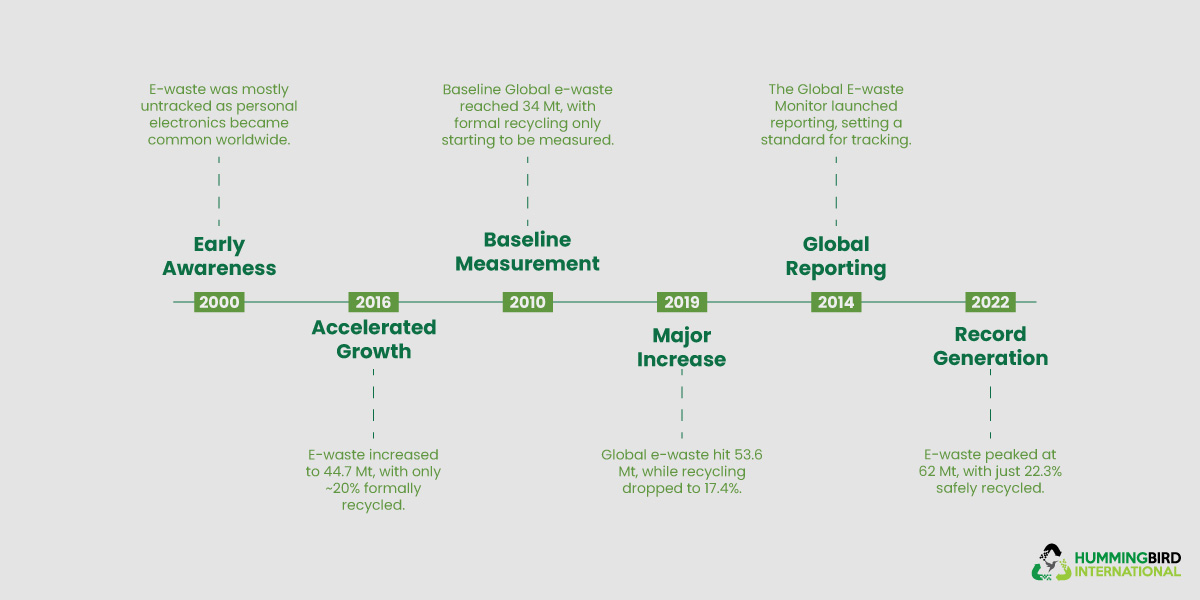

The spike of electronic waste over time

Electronic waste did not become a problem overnight. Like all new technology, its negative impact came be to be recognized once technology became prevalent and IT device and asset use became for common. If you want the bigger “why,” start with planned obsolescence and its impact on e-waste and why reuse and repurposed manufacturing matter.

The numbers behind electronic waste

- Early tracking (2000s): E-waste started getting attention as personal electronics became common worldwide.

- 2010 benchmark: Global e-waste was measured at about 34 million tonnes.

- 2014 reporting improved: The Global E-waste Monitor became the main reference for consistent global reporting.

- 2016 growth continued: E-waste rose to about 44.7 million tonnes, with only a portion tracked through formal recycling.

- 2019 climbed again: E-waste reached about 53.6 million tonnes, and collection still lagged.

- Latest published global number: In 2022, global e-waste reached about 62 million tonnes, with 22.3% formally collected and recycled. (Source: Global E-waste Monitor)

What the data says about e-waste

- Total e-waste keeps rising because devices are replaced faster and more devices are used per person.

- Recycling is improving slowly, but it’s not scaling fast enough to match the growth in volume.

- Most risk happens outside formal systems—in storage, landfills, exports, and informal processing.

E-Waste Growth Snapshot

| Measure | 2010 | 2016 | 2019 | 2022 (latest published) |

| E-waste generated | 34 Mt | 44.7 Mt | 53.6 Mt | 62 Mt |

| Formal collection / recycling rate | ~10–15% | ~20% | 17.4% | 22.3% |

If you want the practical version of “what to do next,” jump to what businesses can do right now. If you want the deeper story behind these numbers, you may also like rethinking e-waste management and what we learned about e-waste (and what’s next).

Understanding the Biggest E-Waste Trends

The data and trends around e-waste remain consistent though the details change by region: more devices, shorter lifespans, and weak collection systems. For a broader view, see our breakdown of trends in e-waste recycling.

1) Faster upgrades and planned obsolescence

The biggest driver is simple: people replace devices quickly. Batteries degrade, repairs cost too much, and software updates stop supporting older hardware. Even when a device still works, the “upgrade cycle” pushes it out early.

This is the core idea behind planned obsolescence: products are not built for long life, so replacement becomes normal.

2) Repair and reuse are still too hard

Many electronics are not built for easy repair. Parts are glued in, software locks out replacements, and spare parts cost too much. That weakens repair shops and makes reuse harder, which means more devices go straight to disposal.

If you want a more hopeful angle, read the rise of repurposed manufacturing and how reuse markets can scale.

3) Recycling infrastructure can’t keep up

Even when people want to recycle, collection and processing systems often fall short. Facilities cost money, need skilled labor, and must follow strict rules. In many areas, the network is thin, so devices never reach a certified recycler.

That’s how devices end up in informal channels. If you’re deciding whether to recycle, refuse, or rethink the whole approach, see e-waste: recycle or refuse.

4) E-waste is both risky and valuable

E-waste contains valuable metals, but it also contains toxic components that can harm workers and communities when handled unsafely. Done right, recycling recovers materials and reduces environmental harm. Done wrong, it creates pollution and wastes recoverable resources.

If you want to understand what’s actually inside devices, read materials inside devices and what e-waste is made of.

How businesses can help reduce electronic waste

If you’re a business, e-waste is not just a sustainability issue. It’s also a data security, compliance, and cost issue. The good news is there are clear steps that reduce risk and keep things simple.

Checklist: before you recycle company devices

- Confirm what devices you have (model, serial, condition).

- Decide what can be reused or resold vs. recycled. (Start here: e-waste as an opportunity)

- Choose a certified partner and require chain-of-custody and reporting.

- Require proof of data destruction. (Learn more: data destruction services)

- Set a pickup schedule for offices and remote teams. (Helpful: multi-location e-waste pickup)

Schedule a Free E-Waste Pickup

FAQs

What exactly counts as e-waste?

E-waste includes any device that runs on electricity or batteries and is no longer wanted or working. That includes phones, laptops, monitors, printers, routers, chargers, and small items like earbuds. For examples, see types of electronic waste.

Why is e-waste growing so fast?

Because devices are replaced faster, repairs are harder, and more people use multiple devices at once. Recycling systems are improving, but they’re not scaling at the same pace as device turnover.

Can e-waste be recycled safely?

Yes—when it’s handled through certified channels with proper data security and downstream tracking. If you’re choosing a partner, use this guide: how to find a certified ITAD partner.

What happens when e-waste is handled the wrong way?

It can end up in landfills or informal recycling, where toxic materials can leak into the environment or be released into the air. It can also create data security risks if storage devices aren’t destroyed or wiped properly.

How do businesses prevent data exposure during recycling?

Use a documented chain of custody, require certified wiping or physical destruction, and collect proof. If you need a direct next step, start here: secure data destruction.

Leave a Reply